In the City Schools: showmanship inspires scholarship.

People walking by Ashburton Elementary School at 3935 Hilton Road on the morning of June 5 at about 11:00 had to do a double take. There, up on the second story roof, a man seated at a desk was reading into a microphone to the obvious delight of several hundred students picnicking on the ground below. (He was reading “How the Elephant Lost His Trunk” from Kipling’s “Just So Stories.”) The man was Robert Marino, Principal, and he was up on the roof this day because he had lost a bet to his students, made at the beginning of the school year: that they would not read, during the year, 8,000 books. They read 8,459 books, meeting Marino’s challenge to them that they could, if they met his “books-read” quota, “send him to the roof.” Which is where, and why, the passers-by that day on Hilton Road saw Marino up there.

Principal Marino was making a point that children from so-called disadvantaged schools and low-income families where reading in the home is not stressed can be persuaded not only to read but to read a lot — given the right incentives. Marino’s roof-top performance is only a small part of a larger package of incentives that are invigorating the currently successful Outside Reading Project.

Since last September (1989), 10 Baltimore City elementary schools have set out to prove that schools can do much to eliminate the dearth of reading in the homes of their students. With small grants ($2,000 each) from The Abell Foundation, these schools have designed and implemented projects to encourage and require outside reading by students.

So far the projects have had resounding success. Virtually every school has successfully implemented an outside reading requirement that has each student reading two books each month. Every school has used a variety of incentives to encourage students to read, and to read beyond the required number of books: typically, the goal of Ashburton Elementary for the school year was 8,000; the students read 8,453.

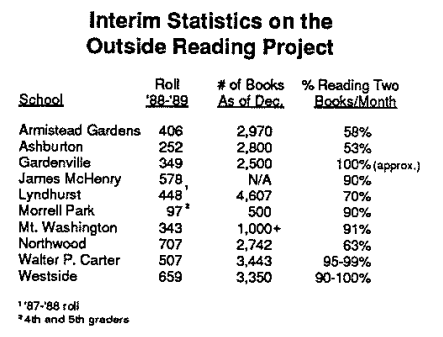

The idea for the Outside Reading Project came from inside a school, Lyndhurst Elementary in West Baltimore. There, with help from the Fund for Educational Excellence and Pizza Hut’s Book-It program, students read more than 8,500 books on their own last year. Lyndhurst became one of the 10 elementary schools selected by the school system for this year’s project. The other schools are: Armistead Gardens, Ashburton, Gardenville, James McHenry, Morrell Park, Mt. Washington, Northwood, Walter P. Carter, and Westside.

These schools were selected from more than 40 elementary schools which put forward creative proposals for how they would use $2,000 grants to encourage outside reading. The proposals included specific plans for incentives, motivational activities and record keeping.

Using funds from the grant, the 10 selected schools purchased various materials to support incentives for students. Many schools post stars or stickers for each book a student reads, a public display of which students are fiercely proud. Ashburton uses sashes and buttons for students to “show off” how many books they have read. In some schools, like Mt. Washington, entire classes can win prizes if they reach certain goals. At Armistead Gardens, the goal this past year was 10,000 books; the students fell slightly short, reading 9,549. Three hundred of the students were treated to the movies; the top five readers went on a sailing trip.

For motivational activities, schools have held various assemblies, to kick off the program, to recognize successful readers, and to continually stimulate the students. Some schools, like Westside and Walter P. Carter, have brought in celebrity readers and well-known children’s authors to inspire students to read. At Morrell Park, students are paired together to encourage each other to read. Each school has developed its own system to both verify that students have actually read the books and to keep track of individual, class and school statistics. Northwood relies on parental signatures on specially designed and printed record sheets. Other schools use short book reports or oral reports for validation.

In addition, participating schools have also had the opportunity to strengthen their ailing libraries, using $1,500 of the grant to purchase new books. Many schools have raised additional money for books. James McHenry has had particular success raising money for its Delores Diggs Memorial Library. (In the 1986-87 school year, Baltimore City schools received $3.00 per student for library books, compared with more than double that amount received by Baltimore County schools.)

While the Outside Reading Project is still incomplete, interim reports written by each school reveal that already the 10 schools have proven some of the basic premises upon which these pilots were founded.

First, the pilot schools have demonstrated that if students are asked to read books on their own and given incentives as encouragements, they will read many books.

Second, the 10 projects have shown that if elementary schools require some outside reading, a large majority of the students will comply. Indeed, schools are noticing monthly increases in the percentages of students reading two books per month.

Third, the project has demonstrated again the power of school-based staffs to make significant accomplishments using their own energy and creativity.

Fourth, the project has demonstrated what can be done with very little money. In the upcoming months, schools will continue to promote outside reading and refine their projects, using lessons they are learning on a daily basis about what works and what does not. Many principals are convinced that the dramatic increase in extracurricular reading will be reflected in improved reading skills, hopefully revealed in standardized test scores.

Support for the value of the Outside Reading Project (or any program designed to encourage young students to read more) is provided by a 1985 study, “A Nation of Readers,” published by the U.S. Department of Education. According to Robert Stevens, a research scientist at the Center for Research on Elementary and Middle Schools at the Johns Hopkins University, the study makes clear that 1) young children who read more early in their school experience enjoy higher achievement throughout the rest of their schooling, in particular, on standardized tests including the California Achievement Test, and 2) young children who read more tend to watch television less, and thus avoid the learning pitfalls often associated with extensive watching of television.

The Baltimore City Public School system is working with The Abell Foundation on a plan to expand this program to 20 additional elementary schools, four middle schools and four high schools, as a prelude to a systemwide promotion of outside reading. From all of the evidence, the Outside Reading program is proving itself a measurably successful, and highly commendable, effort at motivating this special population on the value, and the joys, of reading.