The global COVID-19 pandemic has caused an unparalleled amount of physical, emotional, and financial stress on households and families across the country – and around the world. On the economic side, besides the loss of jobs and income for many, interest rates have also been quite low. That is good for people who wish to buy homes or perhaps refinance mortgages, but for older persons who rely on interest on their savings to supplement Social Security and pensions, these low interest rates mean a reduction in income.

The Abell Foundation, the Reinvestment Fund, and housing advocates in Baltimore were concerned that the economic distress of the pandemic, coupled with the reduction in income, would represent the perfect storm for older Baltimoreans who might be persuaded to take out reverse mortgages, or HECMs, as a way of paying bills. HECMs are loans to older homeowners (62+ years of age) insured by the Federal Housing Administration. They are used to convert equity in one’s home to cash while maintaining the ability to live in that home. HECMs can also be used to pay off an existing mortgage.

While HECMs may have benefits in the right circumstance, they are very complex. HECMs are not without homeowner obligations (financial and maintenance), risk (of loss of home), or cost. They are mass marketed by personalities that are themselves older and present as trustworthy, making the loans seem safer than they may actually be for an older homeowner. Like other waves of lending that harmed borrowers in Baltimore (e.g., subprime and predatory lending), HECMs could also be targeted to communities of color.

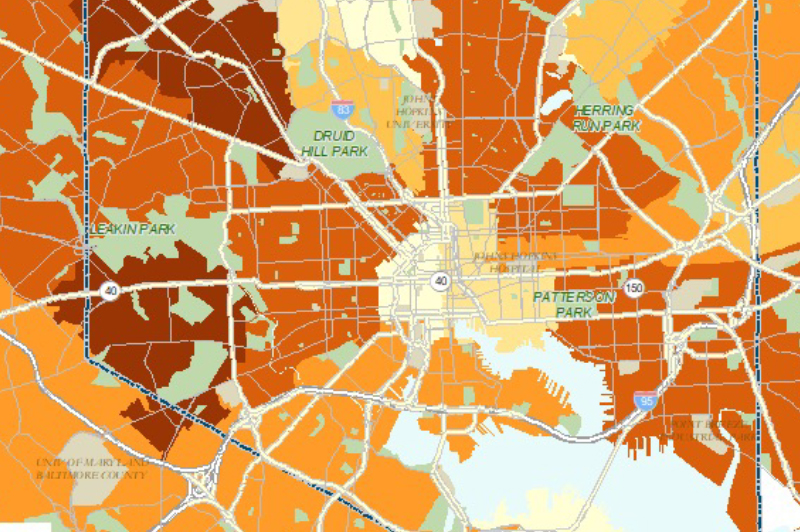

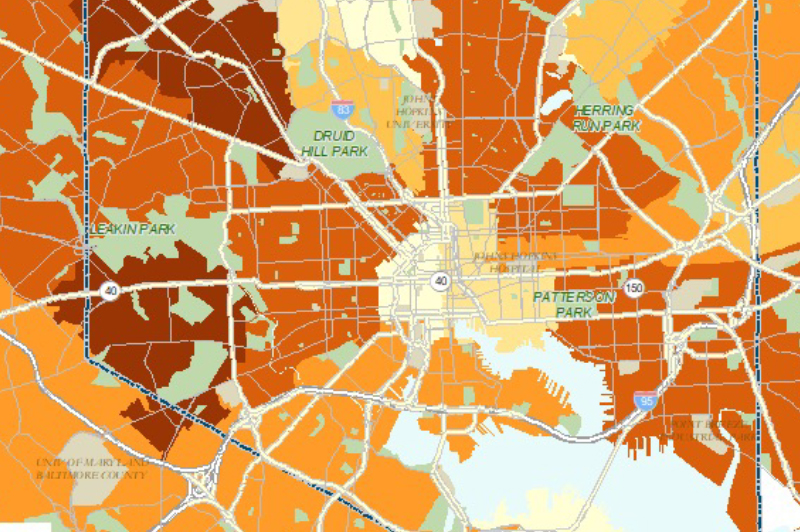

The attached report and presentation chronicles the trends and patterns of HECMs in Baltimore from 2010 through 2020. The data show that the volume of HECMs, while high in the early part of this period, slowed to a trickle in the last few years. And although the early period of lending manifests a concentration in the predominantly Black neighborhoods of Baltimore, the current volume is so low that such patterns are not discernible.

However, this does not mean that the well-chronicled problems with HECMs do not impact older homeowners in Baltimore, most of whom received their loans prior to the underwriting changes around ability to meet financial obligations. HECMs, particularly those made prior to 2017, are understood to be more problematic. Many of these mortgages still exist with the homeowners who got them, and therefore, so too do any prior abusive or fair lending concerns. Nor for that matter does it mean that the approximately 43,000 current older Baltimore homeowners are immune from ending up with a problematic HECM in the future.

Accordingly, the report suggests and recommends: